Insights into Laravel package design

This is a guest post written by Graham Campbell, prominent PHP open source developer and StyleCI founder. This is the third blog in a series on best practices using Composer.

Laravel is a massively influential PHP framework, and its simple but powerful design means that it’s easy to utilize packages in your application. In this blog post we will look at the basics of creating and installing Laravel packages.

Where do I start?

Composer is massively important in the PHP world, and Laravel is no exception to this. The Laravel framework core specifies its dependencies using Composer and so do Laravel applications by default. With this in mind, it is totally natural for our packages to also define their dependencies using Composer, and to be distributed via Packagist using Composer.

For an introduction to Composer and Packagist, you may want to read the previous two blogs in this series.

In this blog post, we’ll be building a small package by means of example. You can follow along with the example here.

The basic structure of a package

At the core of things, remember there’s actually nothing special about a Laravel package compared to any other PHP package. Most people start off with:

- A readme – README.md

- A license file – LICENSE

- A composer file – composer.json

- A gitignore file – .gitignore

- Your code folder – src

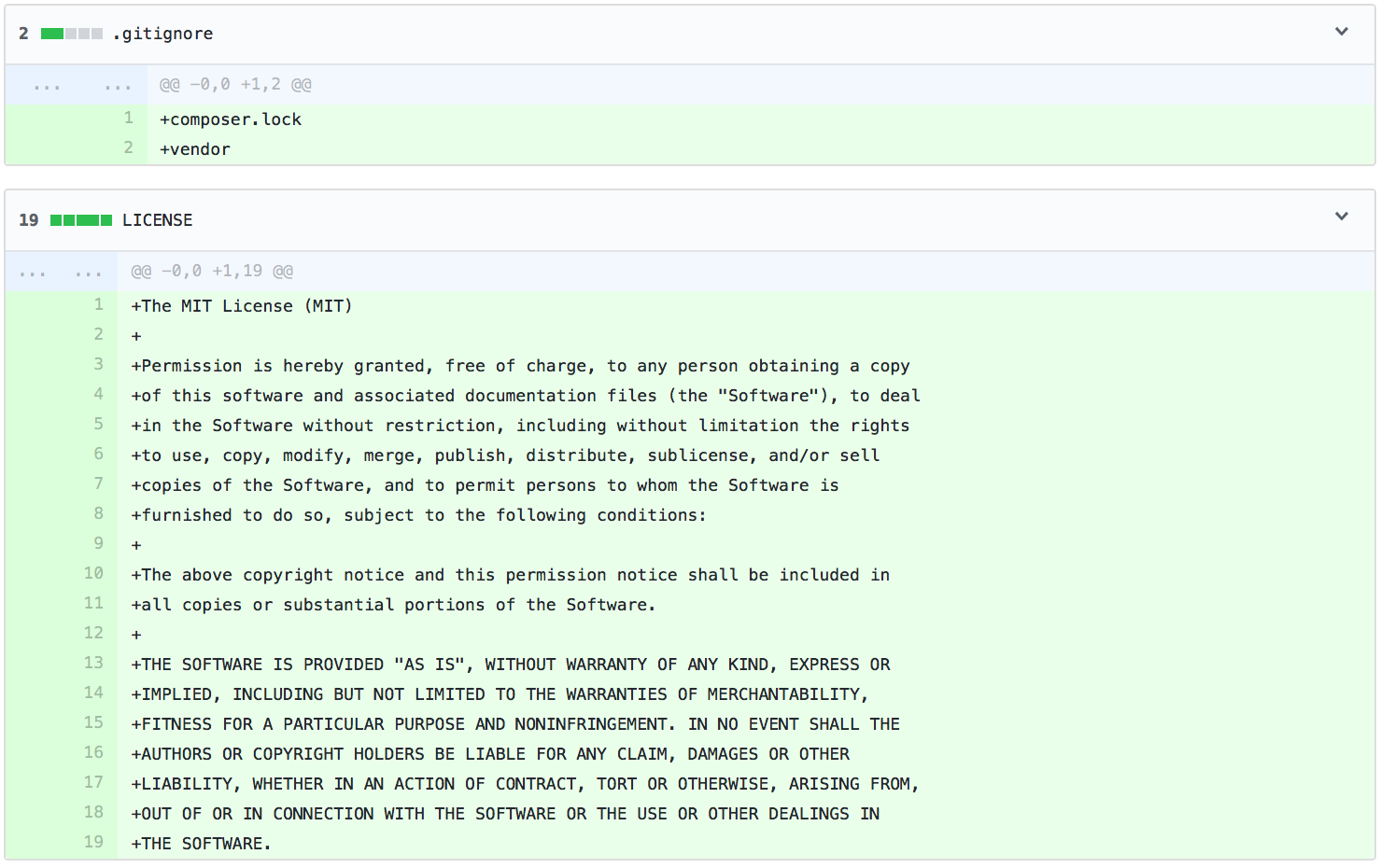

So, we will write a short readme, choose a license, add a basic composer.json file, and a .gitignore file:

We’ve named our package foo-bar/example, and namespaced the source folder to Foo\Bar\Example.

Adding your code

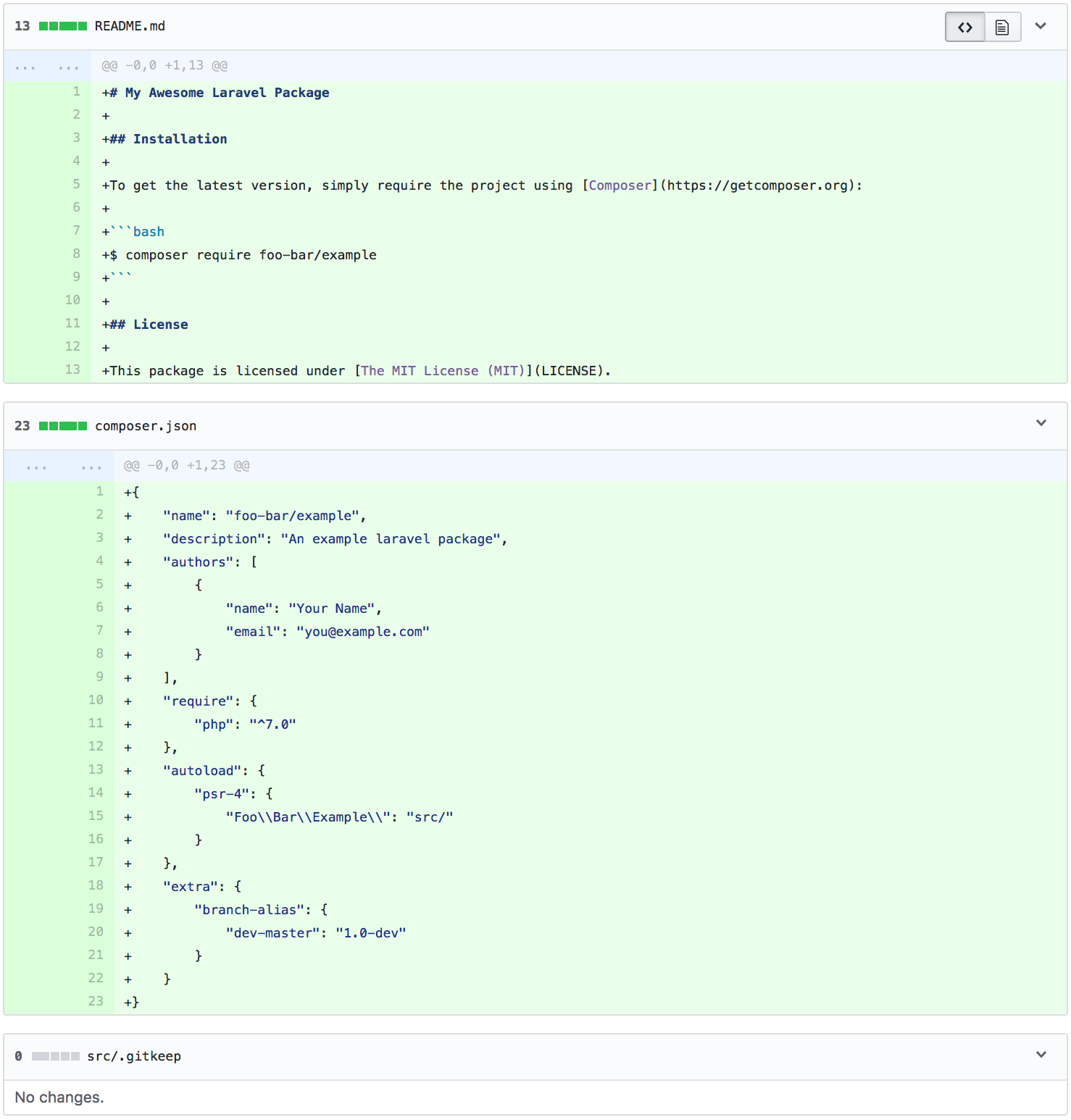

Next we will write a short class that will give us random cat names!

Facades and Containers

Our class can be used in any PHP project, Laravel or not. What if we want to make it available through the Laravel service container, or a Laravel facade?

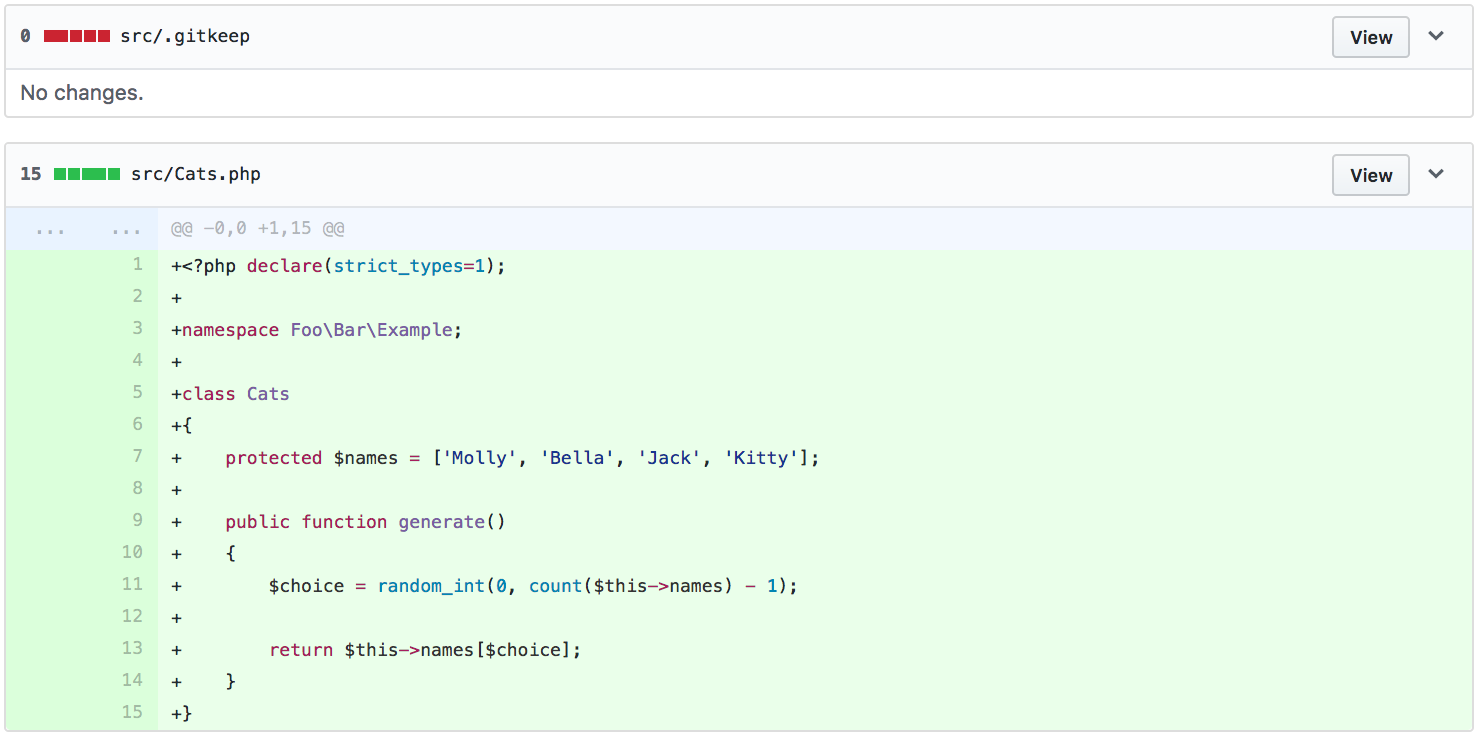

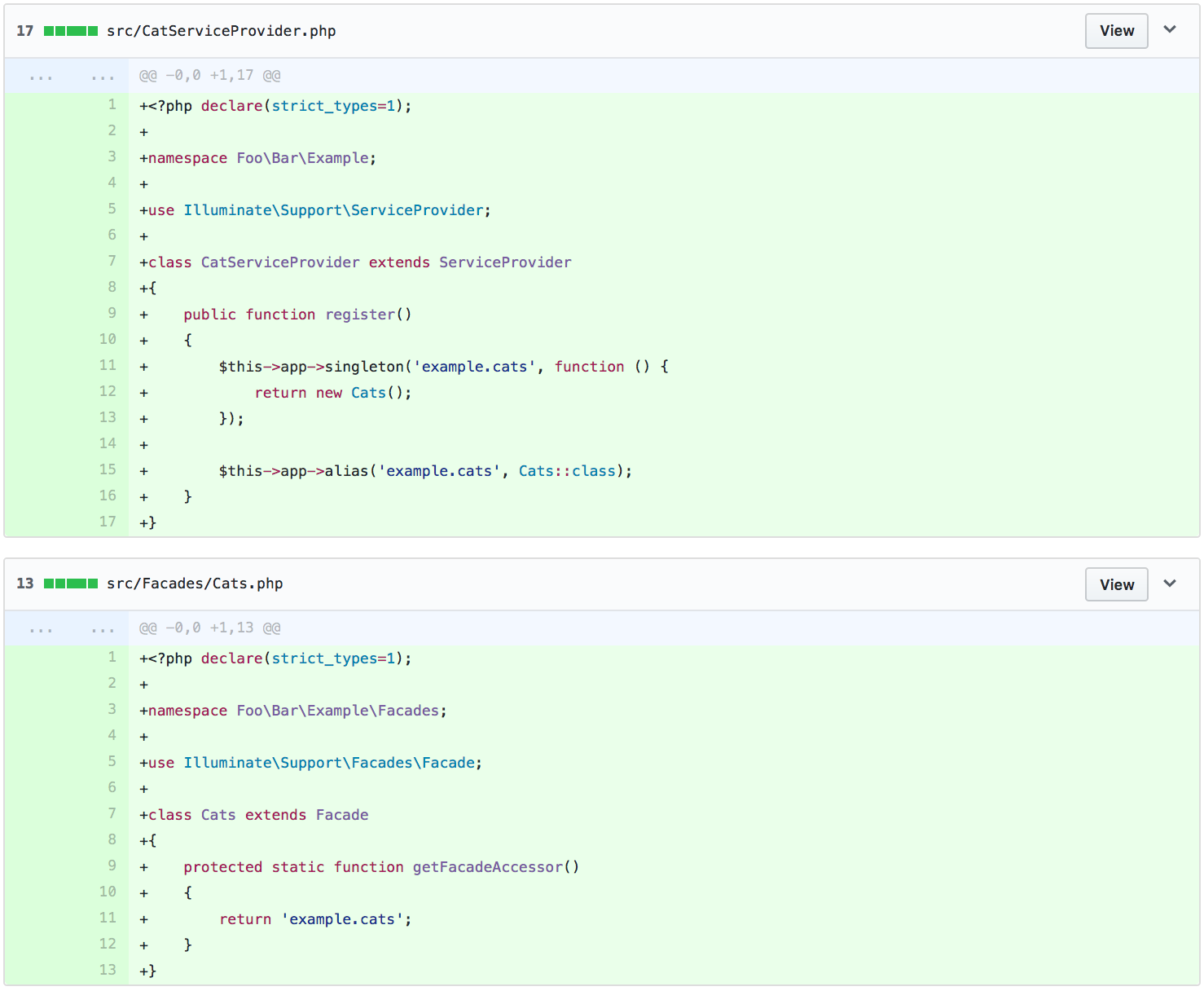

First, we add a service provider. This binds an instance of Foo\Bar\Example\Cats to the service container, and allows us to access it via app(‘example.cats’) and to inject it into classes with a parameter typed with Foo\Bar\Example\Cats. Users of your package can register this service provider in order to setup the bindings.

Your facade means that your package users can now call:

Foo\Bar\Example\Facades\Cat::generate()

or Cat::generate() if aliased or imported.

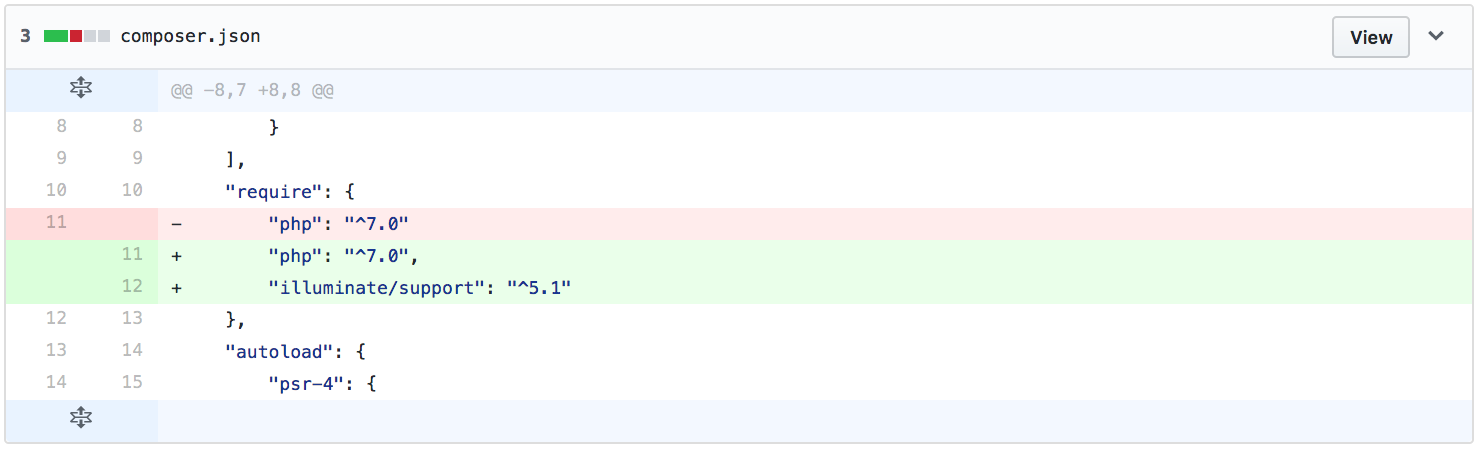

Since we’re making use of the support component, we will require it:

Configuration

Suppose we want to add the ability to customize the names of the cats provided by the generator? We can do this using Laravel’s config facilities.

First, we modify our code to receive the desired names through the constructor. It’s important that we do this rather than trying to read the configuration from inside the class in the interest of avoiding coupling our class to the configuration. One common error I see is to not only couple code where not needed, but more seriously, to make the assumption that the global config function is available for use. You cannot assume this unless you require all of laravel/framework, and similarly, you can never assume Config is aliased to Illuminate/Support/Facades/Config, or even that facades are enabled (in the case of Lumen, or other custom frameworks). Never write use Config; unless you know that alias exists.

So, we modify our constructor:

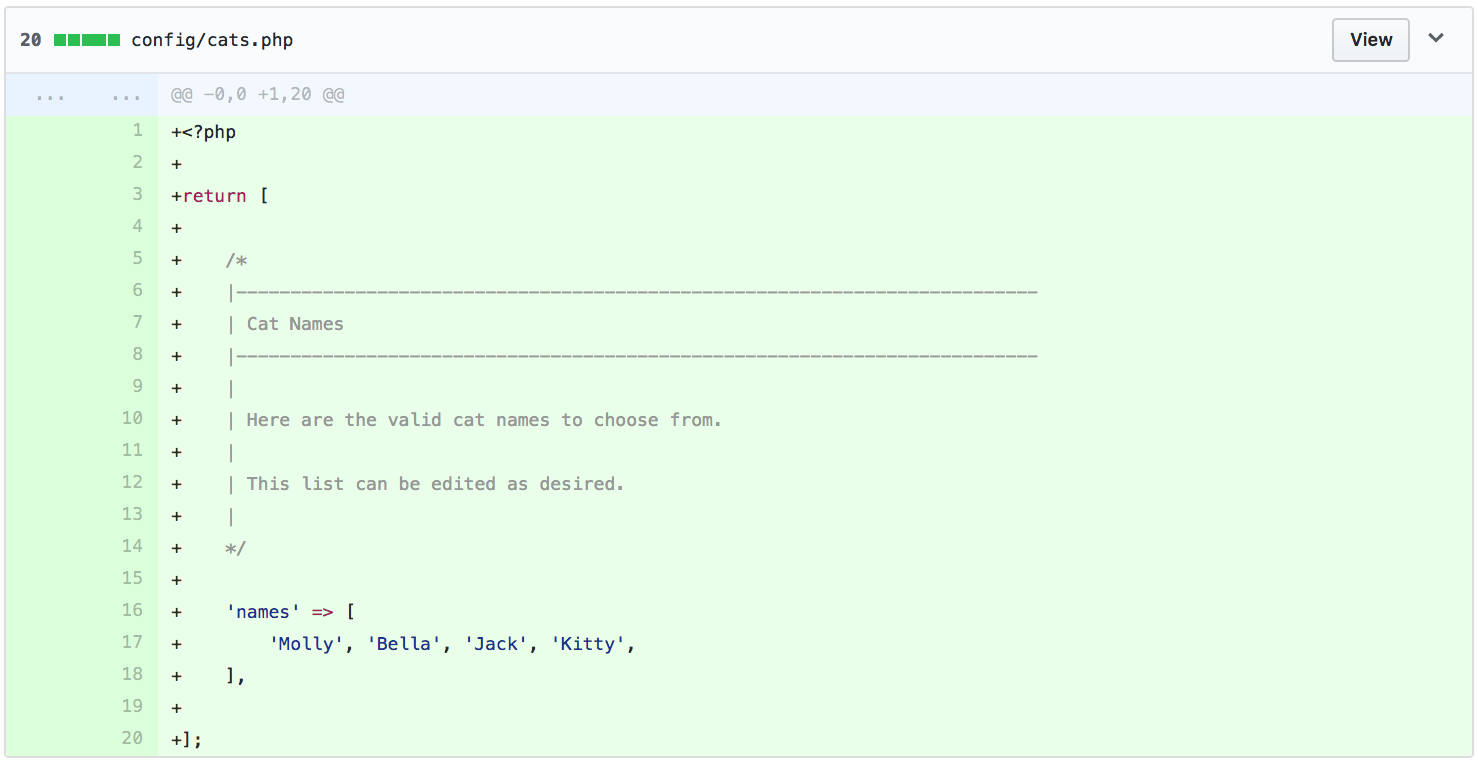

And write a configuration file with the cat names:

Users can publish this file to their application in order to enter their configuration. There is actually no requirement to place this file in this exact location in your package code since Laravel 5 is much more flexible than Laravel 4; however, I think this makes for a good place to put it.

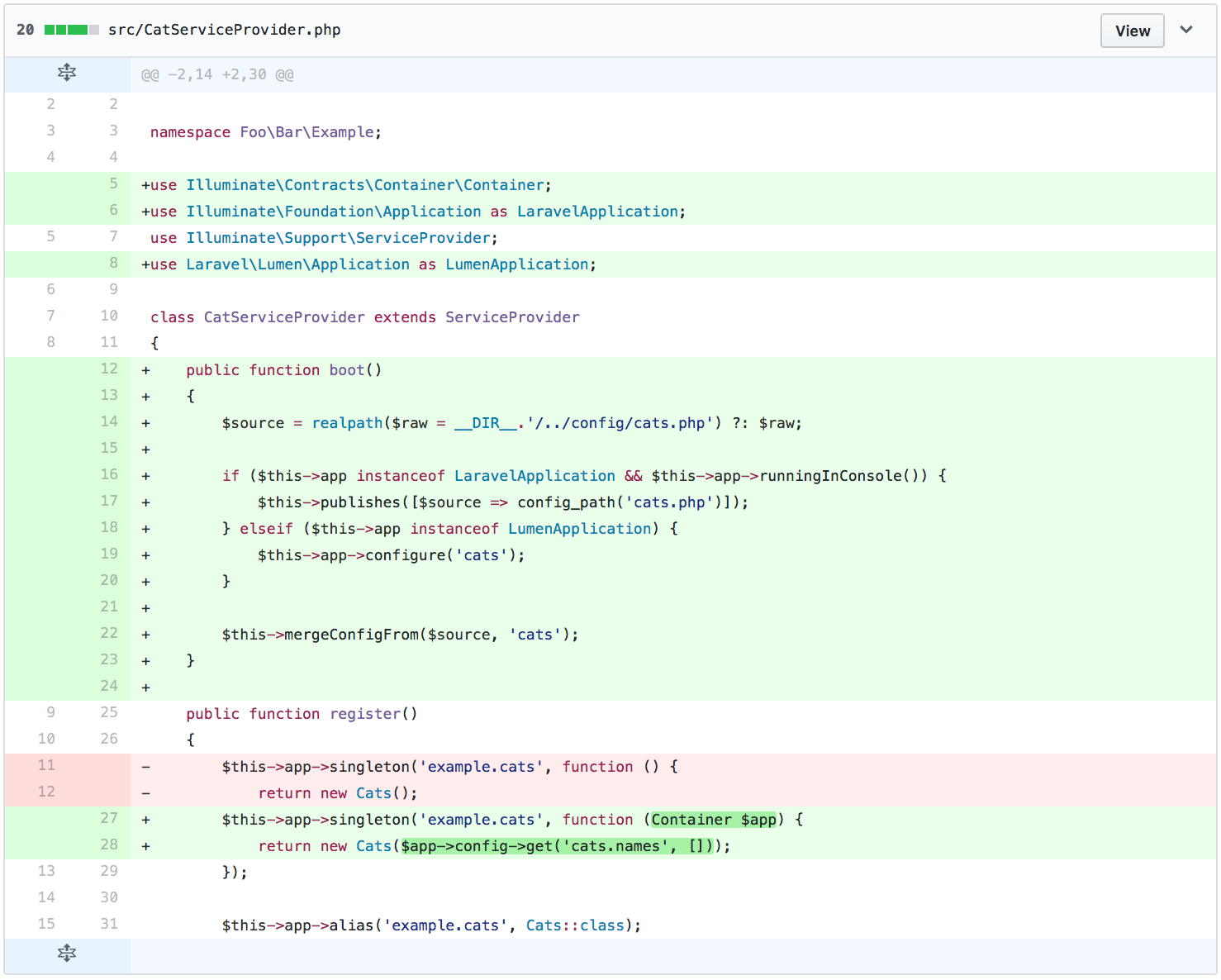

Next, we define our service provider:

There’s a lot going on here! Let’s walk through it. We will start by looking at the modifications to the register function. Since our Cats class now takes an array of cat names in the constructor, we need to pass one. We read the configuration from the file “cats.php”, entry “names”.

Our boot function is needed to register our configuration file with the framework. It’s actually okay to call the global config_path function here, since we only ever enter that branch of the code if we know the container is an instance of a Laravel application, so it must be the case that the whole Laravel framework is there.

One should also note that it’s absolutely fine in PHP to import classes that don’t exist. The only side effect of an import statement is to bind the long name to the short name. With this is mind, it really does mean that PHP doesn’t care if the class doesn’t exist because it doesn’t try to load it. Similarly, in an instance of check, PHP will not bother checking if the class provided actually exists since the implementation seemly needs to perform reflection on the object.

Testing

Before we finish, it is only natural that we take a very quick look at testing.

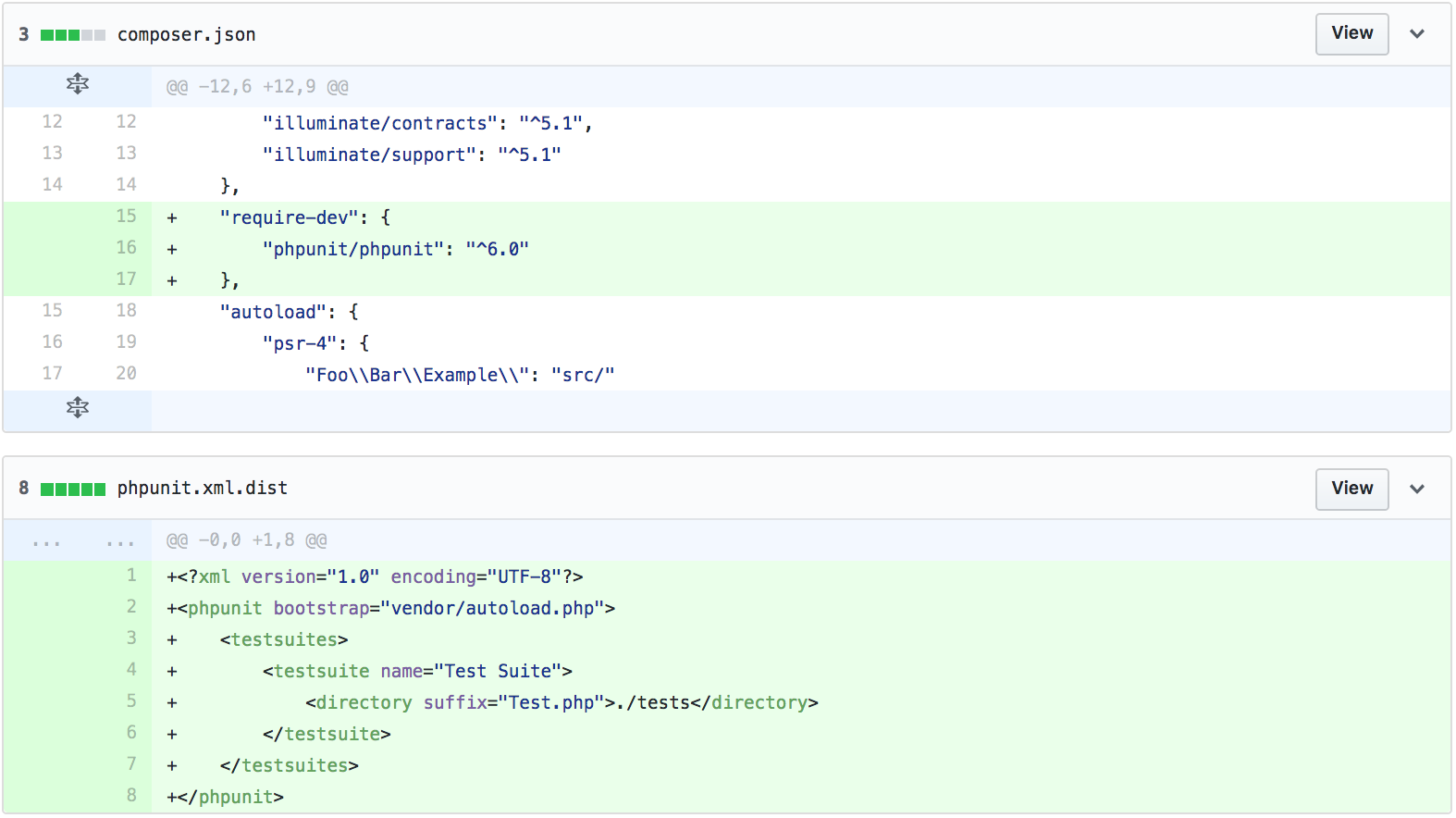

The most widely used framework for this is PHPUnit. This can be installed globally, or added as a local composer dependency.

We pull in PHPUnit, and add a basic config file:

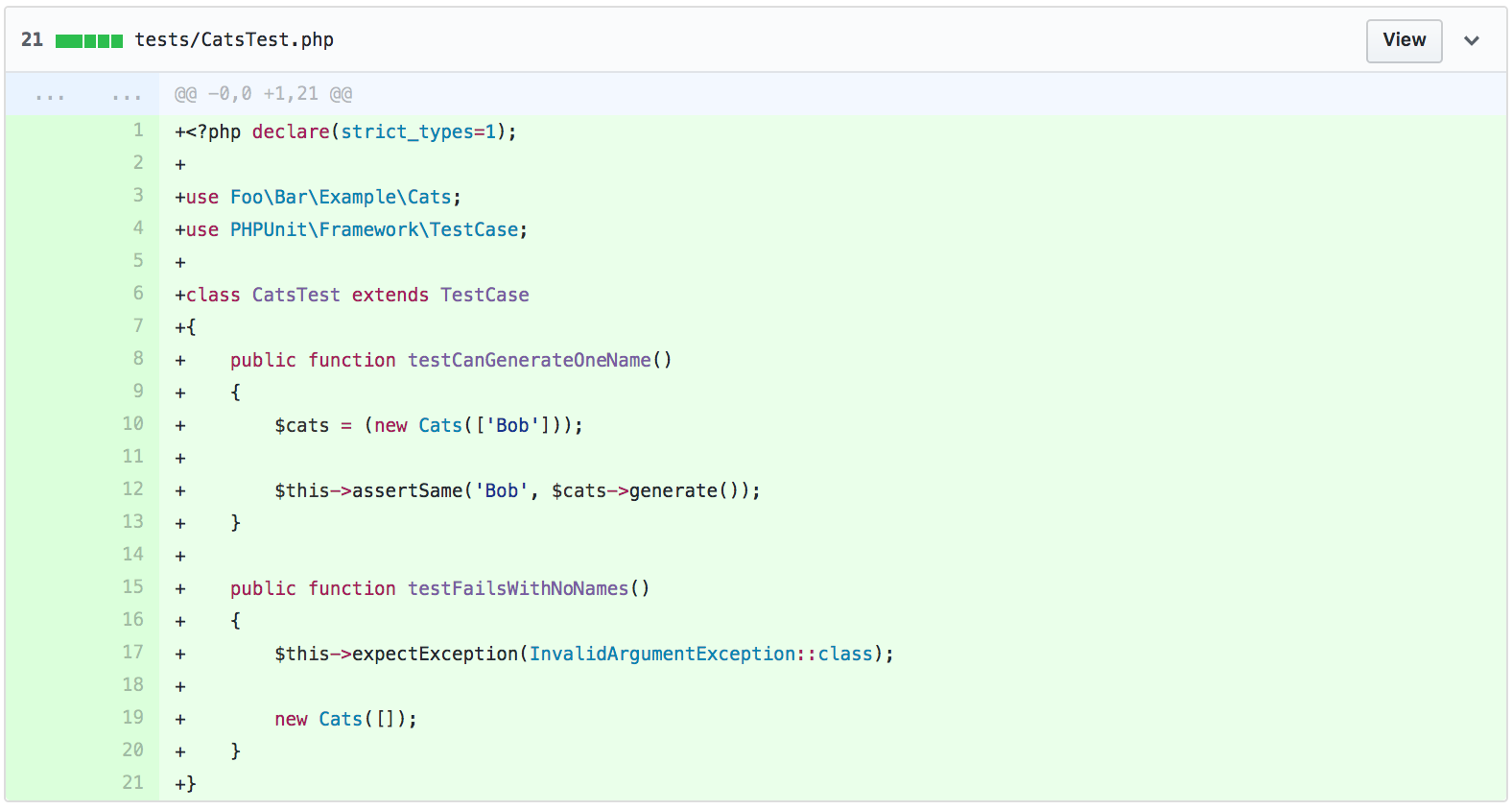

We now write a few simple tests to check if our Cats class is behaving as it should:

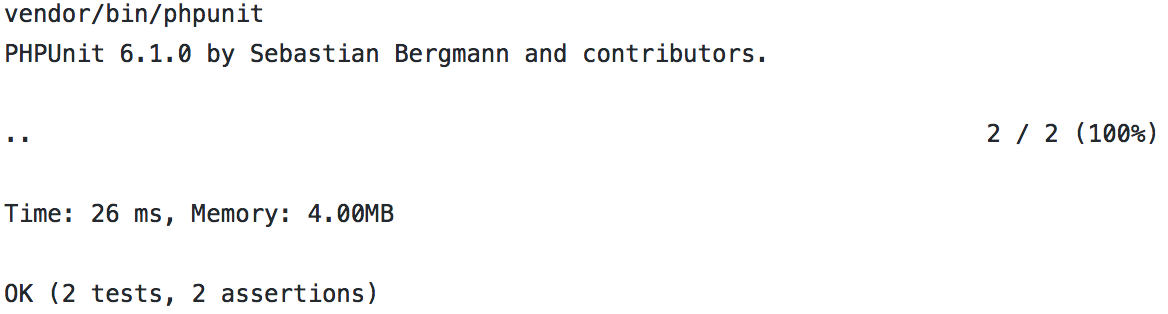

We can run our tests:

Conclusion

We have seen how to write a simple Laravel app with configuration, a facade, and basic tests. Now, go build something great!

———

You can find the Laravel example in this blog post here on GitHub.

Are you monitoring your Laravel application for errors? Try Bugsnag’s Laravel error reporting to gain insight on bugs and fix them for your users.